5 30-min. solos

Premiere:

Brooklyn Historical Society (NYC), September 2018

Choreography & Direction:

Danielle Russo

Producer:

Jenny Tibbels

Technical Direction:

Joanna DeFelice

Makeup Design:

Marc Witmer

Costume Design:

Jenny Lai

Film & Photography:

Luke Ohlson

Performance & Collaboration:

César Brodermann

Roya Carreras Fereshtehnejad

Jason Collins

Kayla Farrish

Molly Griffin

SENTINEL (2017 - 2018)

AN INTERDISCIPLINARY DANCE AND FILM PROJECT CREATED IN DIRECT RESPONSE TO THE POST-ELECTION ATMOSPHERE IN NEW YORK CITY. GRAPPLING WITH INCREASING ISSUES OF SURVEILLANCE, PROFILING, AND ALIENATION, SENTINEL ORIGINATED WITH FIVE SITE-SPECIFIC DANCE SOLOS WHICH WERE RECORDED IN POLITICALLY-CHARGED PUBLIC LANDMARKS ACROSS THE CITY BOROUGHS — FROM TERMINAL 4 AT JFK INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TO PORT RICHMOND, STATEN ISLAND, WHERE MULTIPLE ICE RAIDS HAVE OCCURRED. SPOTLIGHTED IN MAGENTA CLAY FROM HEAD TO TOE, EACH DANCER SHARES A PERSONAL STORY AKIN TO THE HISTORY AND POLITICAL UNDERPINNINGS OF EACH SITE.

AFTER ONE YEAR IN THE MAKING, SENTINEL CULMINATES IN AN INTIMATE INSTALLATION RESEMBLING A SURVEILLANCE ROOM WITH IN-THE-FIELD FILMS ALONGSIDE LIVE PERFORMANCES OF EACH SOLO IMPOUNDED BY A LARGE-SCALE PLEXIGLAS BOX. AUDIENCES ARE PROVIDED WITH HEADPHONES AND AN AUDIOGUIDE PLAYLIST COMPOSED OF PERSONAL TESTIMONIES FROM EACH PERFORMER, RELATED DATA AND REPORTS. WITNESSES ARE INVITED TO MOVE AT-WILL THROUGH THE EXHIBITION, EXPERIENCING THE WORK FROM MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES. ALL TICKETED PROCEEDS BENEFIT THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION.

SENTINEL IS A CALL TO ACTION. IT BRINGS AWARENESS TO LOCAL INCIDENTS OF INJUSTICE—MANY OVERLOOKED OR UNPUBLICIZED—THAT ECHO GROWING TENSIONS AND VULNERABILITIES NATIONWIDE. IT REMINDS US THAT NEW YORK CITY IS NOT IMMUNE TO THE AGGRAVATION AND RISK OF TRUMPIAN POLITICS, URGING ITS AUDIENCES TO REFLECT ON QUESTIONS OF COMPLICITY. AM I AN ACTIVE BYSTANDER? HOW CAN MY ACTIONS INCITE CHANGE?

WORLD PREMIERE:

SEPTEMBER 14 8:00PM - 10:30PM

GREAT HALL AT BROOKLYN HISTORICAL SOCIETY

128 PIERREPONT STREET

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK 11201

PUBLIC TRANSIT: BOROUGH HALL 2/3/4/5, JAY STREET A/C/F, COURT STREET R

TICKETS: $15 ONLINE ADVANCE, $20 AT DOOR

SCHEDULE OF PERFORMANCES:

8:00PM - 8:30PM: MOLLY GRIFFIN

8:30PM - 9:00PM: KAYLA FARRISH

9:00PM - 9:30PM: JASON COLLINS

9:30PM - 10:00PM ROYA CARRERAS FERESHTEHNEJAD

10:00PM - 10:30PM: CESAR BRODERMANN

IN THE PRESS:

FOR ALL PRESS INQUIRIES:

JENNY TIBBELS AT (917)607-4759 OR JENNYTIBBELS.PRODUCER@GMAIL.COM

SENTINEL IS SPONSORED IN PART BY THE GREATER NEW YORK ARTS DEVELOPMENT FUND OF THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS ADMINISTERED BY BROOKLYN ARTS COUNCIL (BAC) AND THE FOUNDATION FOR CONTEMPORARY ARTS EMERGENCY GRANTS.

CESAR

On September 15, 2017, Cesar Brodermann performed his solo segment of SENTINEL in Port Richmond, Staten Island; the borough with the majority of unjust arrests resultant of the January 25th Executive Order ICE Raids neglecting New York City’s sanctuary status. ICE Raids in north shore neighborhoods such as Port Richmond specifically targeted Mexican immigrants. His solo soaks in his experiences as a gay Mexican immigrant, most especially right now.

"This era of politics wants to separate us...I have been in New York City for almost 4 years now, but I remember feeling scared of people on the street and feared being overlooked after the election results. Coming from a Mexican family where being gay was not an option, I have always been scared of being 'too gay' or 'too different'. New York City became a place where I could hold myself without the risk of judgement, but after last November I felt uncertain about behaving the way I did everyday, if I could still hold my best friend's hand on the street.

The color magenta has always held vulnerable meaning for me. They teach you when you are young that color can 'define' your gender. At the start of my performance in Staten Island, there was this little kid and he asked if I was gay. At this point in my life, I don't even think about my response. After I say yes, he goes, 'Ew, he's gay -- let's go,' telling his friends. I felt so attacked but also speechless. What do you tell a 7-year-old kid that already hates? It's about discussion, education, and focusing on younger generations. At the end of the day, we are all human beings."

JASON

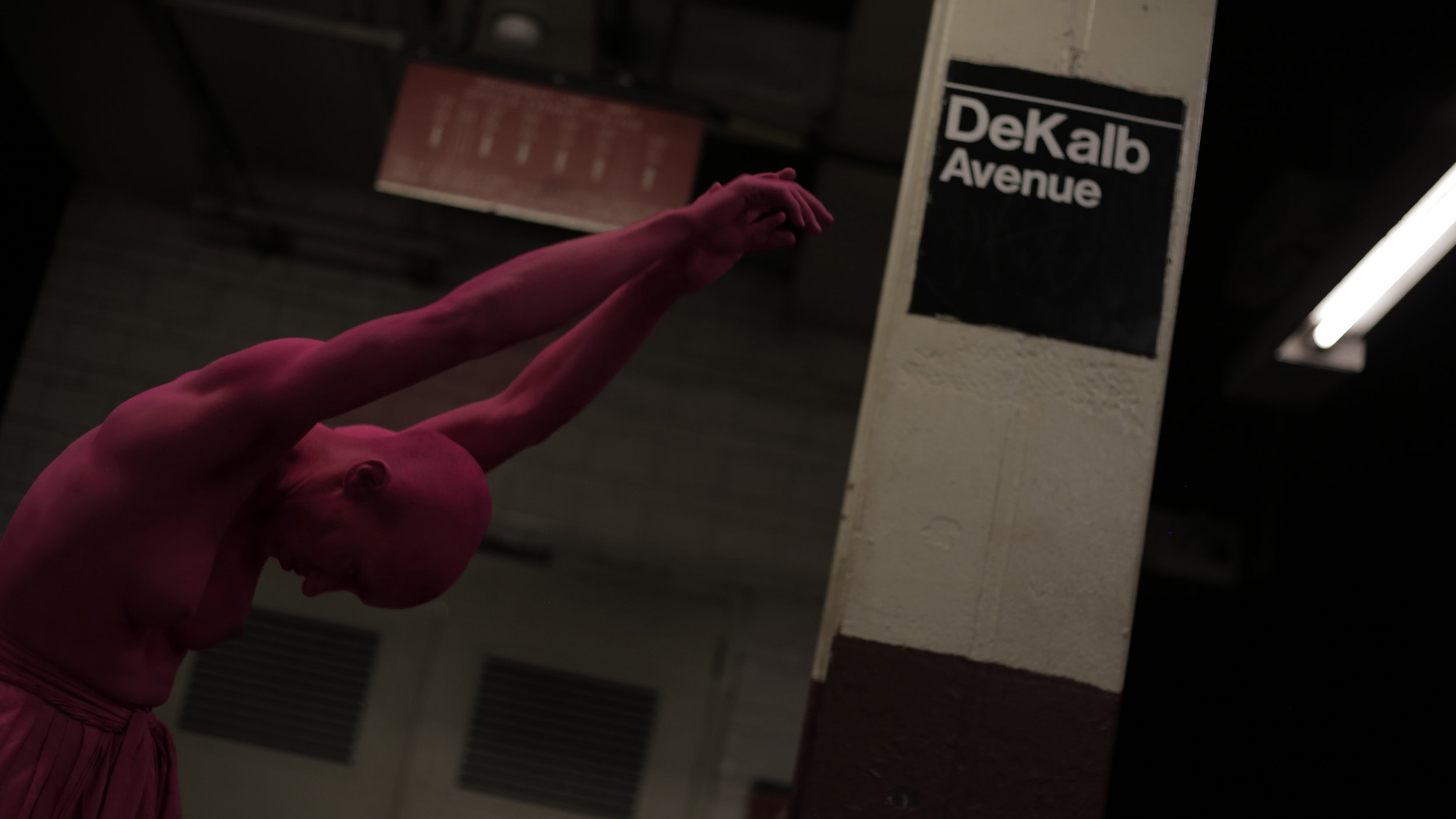

On December 12, 2017, Jason Collins performed his solo segment of SENTINEL off of the C subway line. There have been numerous incidents of reported harassment and assault specifically targeting gay men on the A/C lines throughout 2017. As early as April of 2017, reports showed the number of hate crimes already doubled and the total number of hate crimes regarding sexual orientation already surpassing New York City's records for 2016. As a gay man living off of the C line, and having experienced profiled aggressions firsthand, Jason's performance addressed the reality of his everyday commute.

"I am inherently a person that likes to blend in. It might be a response to being bullied while growing up or just generally feeling 'other' most of my life, but it is no coincidence that I live in New York City because I am addicted to how anonymous I can be here. So, it should come as no surprise that being painted magenta and dancing in public was out of my comfort zone. But, thinking back on my experience while being made magenta in public, I find it difficult to separate this exaggerated experience from my own daily experience.

Since Trump’s election, it has become more and more apparent to me that people feel not only an ability but an obligation to openly hate. I have experienced it myself and I have witnessed it happen to others. Was I more vulnerable painted magenta and dancing on a subway platform than any other person in that station? No. To my surprise, our only difference was that I was an abstraction. I felt just as vulnerable when painted magenta as I do everyday."

MOLLY

On July 19, 2018, Molly Griffin performed on a Brooklyn-bound Q train crossing the Manhattan Bridge. On May 20, 2017, a 24-year old lesbian woman was beaten unconscious in an anti-LGBTQ attack on the same train route. Homophobic slurs over a seat that she and her partner occupied escalated to a violent assault resulting in a concussion and broken eye socket when finally pulling into DeKalb Station. Molly’s performance sought to honor the strength and dignity of the survivor while simultaneously addressing her own experiences living off the Q Line where she and her partner have been combatively targeted.

“This last year and a half in the Age of Trump added a new level of stress that is hard to fully express. I cannot imagine what people of color, immigrants, and other minorities are experiencing. My relationship with New York City and its inhabitants has changed. I feel much more alert and on guard. Reading and firsthand experiencing this sort of violence has caused me to be much more aware of when I hold hands with my girlfriend; where and when we can act like a couple.

What felt most important to me was the act of claiming and taking space. As a queer woman, I often feel that I do not have the right to physical space. So many people actively looked away when we were filming. People can be very quick to disengage with things happening around them in the city—the ‘bystander effect.’ No one intervened when this woman was knocked unconscious, left with a broken eye socket and stitches. When my girlfriend and I were chased down the street by a man screaming physical threats at us, no one stepped in to try and help. And, she and I ride the Q train every day to get home. Here was a woman beaten unconscious because she was gay and taking up space. We were rattled.”

ON MAGENTA

We chose the color magenta because it is not a primary color; it can only exist through the integration and coalescing of many colors. Up until the mid-twentieth century, pink was regarded as a strong, assertive, and virulent color oftentimes affiliated with young boys. While red was associated with notions of hyper-masculinity, pink was seen as its descendent. However, at this point, two things changed: (1) Nazi Germany began labeling individuals accused of homosexuality with pink triangles (a symbol later reclaimed by the gay rights movement of the 1980s and 1990s, particularly by ACT-UP); (2) this shift towards affiliating the color with sexuality and gender–distinctly the effeminate–caused a shift in marketing amongst Western consumers. Gender-coded clothing took hold amongst the Baby Boomers. It became a very lucrative marketing ploy in which consumers who wanted to be a part of the new trend were forced to purchase new gender-colored items for their children. And, in doing so, perpetuating a rigid gender binary laden with significant prejudices.

Today, pink is still regarded as a passive, vulnerable color in Western cultures. Additionally, neurologists finding red as a behavioral trigger accentuate emotional associations, most commonly seeing red as a mark or target for aggression. It is our intention to reclaim our perception of vulnerability; to reveal its power and resilience. The painted bodies are intended to protrude out from the mundane scene of a neighborhood or subway car in an effort to show the day-to-day, enduring presence of our vulnerabilities, especially in this new era of politics. The clay dually abstracts the body–making it seemingly alien–while in fact exposing its very true, naked measure. How strange when the pure, shared human form can seem so distant and otherworldly.

KAYLA

On October 22, 2017, Kayla Farrish performed her solo segment of SENTINEL at the intersection of Eastern Parkway and Classon Avenue in Brooklyn. The discussion and decision of site location was an ongoing conversation from the very start of our process. We decided upon this location not only because of its devastating significance, but also due to the lack of news coverage and response. On September 7, 2017, a noose was found on a tree at said intersection. Exactly one week later, a second noose was found on a tree at a nearby division of the Brooklyn Public Library. The city has made minimal efforts to address these incidents, not to mention removal whereas a majority of the rope has been left on the tree at Eastern Parkway. Kayla's performance sought not to exploit nor sensationalize the dangerous degree of these events. Rather, her dance was –is– a call to action.

"As a black woman and artist, I have felt and experienced more and more aspects and facets of society’s standards for race, class, and gender. Seeing power at both high levels in major events such as unjust police brutality and mass incarceration, on towards a smaller day-to-day sense of accommodating and making my presence non-threatening to move forward. There are stories and images that I can’t get out of my head...I have a lot of rage, grief, and sadness about these moments and our push for change. It’s hard to bring your voice forward, or have the opportunity to do so. We discussed a great deal about requiring society's accountability. I absolutely believe in that. And while performing this solo next to where a noose was tied up, I could feel waves of keeping my power and truth and requiring this accountability looking forward into the eyes of people walking by. And then I would experience this desire to shrink or to soften to make others feel comfortable. To look down so that they could look at me.

I often wonder what happens to the voice of the black woman. I see and hear all this violence against black men. I see archetypes of black women, but I hear less of their voices and experiences. We are generous, giving, compassionate, malleable, and strong...In the solo, there was a repeated gesture directing to my pelvis and reproductive center, gripping and shaking. I continued this gesture for a long duration looking out for that needed accountability. Our rights to our bodies are governed, as our bodies continue to be objectified and politicized. It is my body that has this powerful capability for choice and for life. It was a huge decision to perform this work topless. The thought of being topless, painted fuchsia pink in public, made me a bit nervous at first. However, I felt strong in the form of my body. I felt empowered and capable, and my dance honored women and all people of color.

There is an increase in outright hatred and discrimination, and that can be attributed to Trump’s little discretion and permission for public prejudice. As a person of color, there has always been oppression and discrimination, and I did not believe this would change suddenly. However, I will not allow this hatred to be accepted nor go unaccounted for. I feel like much of my public demeanor or ways of surviving through various power dynamics and societal hierarchies had been taught to me at a young age. As people of color, we're taught to accommodate and assimilate to survive and succeed, and to live. I've grown more scared for my family in the South; I am just scared for all my family members and loved ones. Who knows what wrong time or place we have to be in. My father lives alone in Chicago for work right now, and it scares me that he is on his own. I worry for his safety. I felt the necessity of this process, this work –to perform with empowerment in the face of a symbol of terror and discrimination. And to bring attention to such a specific place and event, to bring attention to our time –what has changed and what has not, and what is continued to be allowed within our society."

ROYA

On January 28, 2017, nearly 2,000 people gathered in protest of Executive Order 13769, commonly known as the Muslim ban, at John F. Kennedy Airport’s Terminal 4 where several individuals were already detained. On March 4, 2018, Roya Carreras Fereshtehnejad performed on the same protest grounds at Terminal 4. As an Iranian-Hispanic woman raised in a Muslim home, her dance confronts the crisis and complexity of identity, heritage, and profiling on a most personal level.

“I felt a lot of fear and deep disappointment when Iran was declared on Trump’s travel ban. My father was supposed to fly to Iran to visit family only a week after the ban was first implemented. When things like this happen, you immediately think of the worst-case scenario. Will he be okay? Will he be bullied? Will he lose his citizenship? Will my grandmother, cousins, and nephews be safe in Iran?...

I was born and raised in this country, and yet, I am not allowed to feel American. I do not ‘belong.’ I am not protected. On 9/11, I remember crying over breakfast with my family and debating about whether to go to school or work that day. This was not because we were afraid. Rather, we were heartbroken. And in that moment, I could not fathom what was to come. So vividly, I remember walking into my math class. The teacher turned off the television as soon as everyone was seated. Once the class got quiet, he looked at me and said, 'How do you feel about what your people did to us?' I couldn't believe it! I sank into my chair. Most of the class went quiet but some laughed. I left for the bathroom, balling. I never went back into that classroom. I left all my things. Called my father from the school office. Switched classes and forever avoided that man. I truly didn't realize I was an outsider until then.

My sexuality and my heritage have always been a conflicting topic for me. I grew up with an extremely liberal mother while submerged in a first generation Muslim home. I was not allowed to dance until I lived with my mother. I was not allowed to experience what most American children experienced. I was raised to be hyper-sensitive of how I looked, how I dressed, and the attention I was drawing in. As a teenager I felt ashamed of my body and had a conflicting desire to both express myself and also hide. This translates into a difficulty of practicing self love; how can you love yourself if you are constantly hiding or accommodating an outside perspective?"

ON-SITE PHOTOGRAPHS & FILMS BY LUKE OHLSON

REHEARSAL PHOTOGRAPHS BY STEVEN SCHREIBER & KAYLA FARRISH